-By Jay Murdock, SDKC Safety Editor

On January 28, 2017 a Whale Watch Paddle was scheduled, but was postponed because of possible unsafe conditions at the mouth of the Mission Bay channel. Swells of 6-7 ft were predicted, and an ebb tide going out the bay off a 5.89 high tide at 9am meant that conditions at noon, when we would be coming back in, may create breaking waves of 8-10 ft. Five of us paddled out to the entrance that morning to check on what was actually occurring.

The west end of the Mission Bay channel can pose a real challenge for paddlers at times, and has been compared to the harbor entrances in the Pacific Northwest. Because it faces almost due west, it is vulnerable much more to the effect of swells, winds, and currents than our “Big Bay” entrance, which is protected by Pt Loma. Before the Mission Bay channel was dredged and the south jetty extended in 2010, the mouth was extremely dangerous during storms, with waves breaking the entire width of the entrance. Several boats have sunk there, from surf kayaks to 35 ft fishing vessels. The challenge to the paddler is to know when it is safe to paddle out the entrance and re-enter at a later time of the day. What may seem easy on the way out, can turn into an unsafe situation on the return leg. The key to a safe paddle is knowing how to predict the conditions at the mouth on both legs of the paddle. It is easy to turn back before you reach the mouth while on the way out, but you may find yourself in harm’s way coming back in.

Factors to Consider before you paddle

The San Diego Fire-Rescue Department (city lifeguards) have advised us to not paddle out of Mission Bay when the swells are 7-8 ft and higher. Our challenge is to judge when those threshold conditions will be. The factors that affect swell (wave) height at the channel entrance are tides, winds, swell direction, and swell period (interval) at the time of our paddle.

Tides

A strong ebb tide flowing out the bay causes the swell height to increase at the point where they meet, so you need to know when the high tide is, and the height of that tide. The higher the tide, the stronger the ebb outflow current is, and the higher the waves become at the entrance. The “Mean High Tide” for Mission Bay is 4.8 ft. The “Mean Higher High Tide” is 5.5 ft. Anything above that causes quite an outflow. Think of it as a river flowing out to the ocean. When that flow meets the incoming swells, it forces them to not only get higher, but also closer together, making it much more dangerous to boaters. That danger increases toward the end of the ebb tide, as the water level becomes shallower.

Winds

On occasion we have strong northeast (Santa Anna) winds that can cause problems in the channel, but the main consideration is winds from the south, west and northwest associated with strong storms. That wind can increase the probability of high swells that spill over at the top, adding to the difficulty of paddling through them. High winds also just make it harder to hold a course, and can blow us against the jetty. Wind is often the factor that turns a comfortable paddle into a stressful and possible unsafe event. Sustained or gusty winds over 18 mph can be hazardous, and should be reason to cancel the paddle on big water. Even with little wind, the other factors can still make paddling through the bay entrance something to ponder. At the end of this article is a weather website for hourly data, giving several factors which include the wind strength and direction. There you can drill down to what is going on at a particular day and time. You need to check that the night before you paddle to get the most accurate data.

Swell Direction

Swells head to our coast from different directions, depending on the area of the ocean where there are high winds that create the swells. We usually have swells coming from 2 directions at the same time. Look for the “Combined Height” readings to see what the synergetic effect is, which is a high mark indicator. There are also wave angle arrows that will give you the direction they are going.

Swell Period

Often ignored, the swell period, or interval, is an indicator of the energy of the swells. That is the interval between the crests, or how far apart the waves are. Long period swells have more energy than short period. The higher that number is, the higher the swell becomes as it enters shallow water. A 3 ft swell with a 10 second period may only grow to a 4 ft breaking wave on a beach, whereas a 3 ft swell with a 20 second period can grow into a 15 ft breaking wave. I’ve listed some web sites to get this information, and I really like the wetSand site, as it gives detailed graphs to see what swell height, swell direction, swell period, tide, and wind is predicted for a given day and time. Placing your curser on a particular bar will give you the details. If you know another good site beyond those listed below, please let me know, and I’ll add that to this article.

How to Safely Re-Enter the Channel

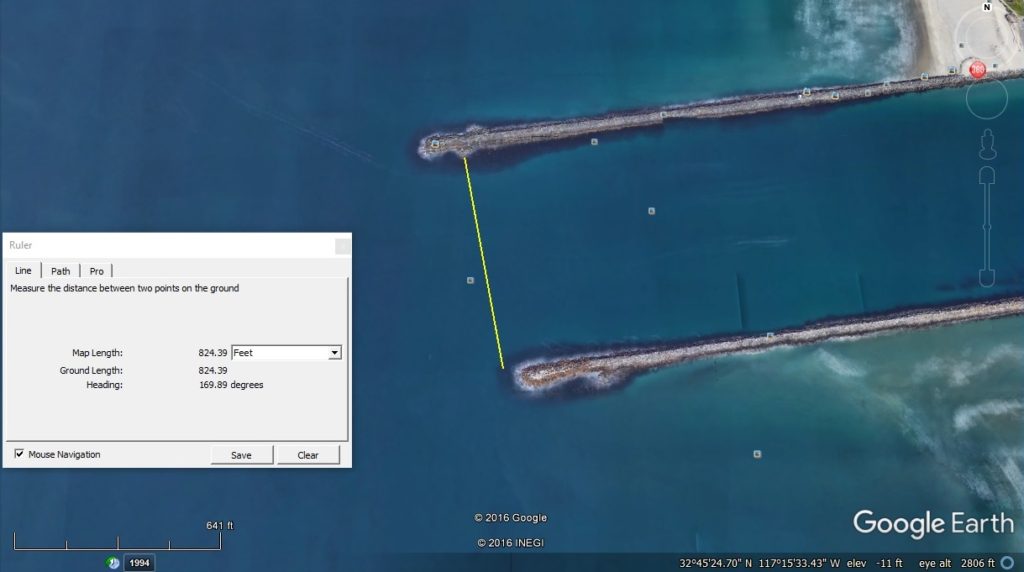

The channel is much deeper in the middle half of the 825 ft width than it is near the jetties. The depth of the middle channel was 20 ft as of 2013 on the most recent NOAA Fathom Chart, and 9 ft at the sides. Swells are much more likely to crest and break near the jetties, and bounce off, making the water very turbulent some distance from them. If the swells are coming from the northwest, you will see them break on the inside of the south jetty. If you are heading in near the south jetty, you need to stay away from those waves, while also staying out of the very center of the channel to avoid being run over by a fast-moving large vessel approaching you from behind. But, because of the direction of the swells in this case, it would be safer to enter near the north jetty, as that is where the protected water is. Before you enter the mouth, look at the conditions and any boats heading in, then make note of your planned point of re-entry. The safest line of travel is at the edge of the deeper water, not too close to the jetties, and away from the center line of deeper navigation water, where large boats steer to. An easy way to estimate where that line is, when on your approach, estimate the center of the width between the jetties, then estimate the halfway point from the center to the jetty you want to paddle close to. That is the edge of the deeper water.

Judging Wave Height

It is much more difficult to assess the size of the cresting swells from behind, but you can get an idea by observing how much of the land background disappears behind the wave. Sitting in a kayak, our “eye level” is about 2.5 ft to 3 ft. When a wave rises to that height you can use that as a “scale” to judge the total height as it grows higher. You can also use the jetty itself to get an idea of the wave height, but you need to take into account the ocean level as it relates to the tide at that time. Waves going halfway up the exposed rocks at low tide are much higher than those at high tide.

Timing the Sets

Swells created by wind in different areas of the ocean have a tendency to sometimes combine with another swell, creating a larger swell. These larger swells often travel together in “sets” of 2-10 swells. It is important before you re-enter the channel to look for these sets, time the interval between sets, and note how many are in a set. Right after a set passes under your boat is when you want to paddle fast into the channel entrance. The interval between sets can be 5-15 minutes. If you can’t wait to “time the sets”, use 5 minutes, which should suffice to get you through the hazard zone.

Paddling through the Chop

Our boats are more stable when underway than when stopped. As you enter that rough water at the entrance, keep moving fast, which will also get you through that area sooner, and take you to calmer water on both sides (east-west) of the entrance.

What We Actually Found on January 28

The wind was not a factor that day. The prediction was for NNE 14 mph winds in the morning, calming to NNE 5-7 mph. We paddled out the entrance around noon, and came back in around 1pm. While we were right at the mouth heading in, a set of 6-7 footers passed under us, with no breaking crests. From all the recent storms, the concern was that a significant amount of silt may have made the channel shallower, but there was no indication of this. Since the center of the channel was deepened in 2010 the concern now is the areas closer to the jetties. Paddlers have recently seen the crests appear to break toward mid-channel, but that was on days of higher winds coming from the west quadrant. The force of that wind can cause the crest to foam up, which may appear to be white caps. A quarter of the way across the channel from each jetty is where the deeper navigation water begins, and breaking waves can occur from the jetty to that point with swells of 8 feet and larger. Swells over 10-12 feet without a strong wind can break all the way across the channel, and present a real danger to navigation.

Additional Information Learned on February 11, 17, & 18:

The following 4 photos were taken on 2/11/2017 between 1pm and 2 pm when the swells were over 8 feet at 13.5 seconds against a strong ebb tide off a 6 foot high mark at 9am. Sets were between 5 and 8 minutes apart. Northwest winds were between 14 & 18 mph, with only scattered whitecaps. Had the outgoing sailboat been 100 feet to the west when that photo was taken, it would have been slammed by that wave in mid-channel. Using the people in the cockpit as a “scale”, that boat is between 35 and 40 feet in length. Using that as a “ruler”, the height of that wave is estimated at between 10-12 feet high*, which makes sense, given these clashing conditions of ebb tide, swell height/energy, and wind. We now have proof of the threshold conditions that can cause large breaking waves across the channel mouth. During this time two small power boats were seen heading out, then turned back to the safety of the bay.

Click on photos to enlarge.

The following photos were taken on 2/17/17 and 2/18/17. The first photo is late afternoon on Friday when the swells were just over 12 feet from the southwest. The channel was still navigable to larger boats, even though there were winds of up to 40 mph. The other photos were taken on Saturday just before 6 pm, with swells of over 18 feet at 14 seconds. Tide and wind were not a factor, but these high swells were from due west with considerable energy. Using the south jetty 10 foot high light pole (the length of the pole, including the base) as a scale gauge**, these conditions created 15-20 foot breaking waves at the mouth. This is why the Mission Bay entrance is so dangerous at times.

While the advanced kayaker considers the mouth of the Mission Bay channel a great place to play and hone one’s skills on a challenging day, this information is primarily intended for the rest of us for a knowledge base to keep us from harm’s way. Paddle safely.

*- Wave height estimates are given as measured on the face of the wave (from trough to crest), not from behind. For our purpose as kayakers, the Bascom method is used.

**-USCG data lists and NOAA chart data give the height of navigation lights in relation to the mean high water shoreline level so boaters can judge their distance to that light and hazard.

Resources for information and building knowledge:

http://sailflow.com/widget/93759

http://lat360.com/ (new wetSand website, do a copy-paste)

http://www.swellinfo.com/surf-forecast/san-diego-california-south

http://www.ssd.noaa.gov/goes/west/weus/h5-loop-ft.html

http://magicseaweed.com/Mission-Beach-San-Diego-Surf-Report/297/

http://www.charts.noaa.gov/PDFs/18765.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaufort_scale

http://www.surfline.com/surfology/surfology_forecast2.cfm

http://www.srh.noaa.gov/jetstream/ocean/waves.html

-Contributed by Jay Murdock on 2/1/2017